How clean is the air you breath on airplanes?

Dr Aniebietabasi Ackley on 2022-12-22Dr Aniebietabasi Ackley says that during boarding and disembarking an airplane is when you are most likely to breath low quality air compared to when cruising at high altitude. This is due to little circulation of fresh air during these periods and the likelihood of directly inhaling a cloud of infected exhaled air from another passenger.

The recent global COVID-19 pandemic brought concerns about the likely transmission of infections on board airplanes back into the limelight and highlighted the importance of good ventilation (clean air) as a mitigation strategy for airborne transmission of viruses.

Areas of anxiety have been spaces such as homes, places of worship, schools, buses, trains, and cruise ships. Also, the quality of the air in airplanes has been largely speculative.

Having been involved in a range of ventilation studies in buildings, I was curious about how clean the air on planes is. During an overseas holiday in winter 2022 (southern hemisphere), I carried out a fun activity, where I used electronic monitoring devices to measure carbon-dioxide levels (CO2) on planes, to understand cabin air quality/ventilation.

Though this was initially set out as a fun activity, but following discussions with friends, colleagues and peers, it became apparent that there seem to be a wider interest on this subject, so I decided to formalise my experience into an article that may benefit a wider audience.

My observation was divided into three routes and flight times/duration as shown in the table below:

| Flight Duration | Port of Departure | Port of Arrival | Airplane type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 hours | Wellington, New Zealand | Melbourne, Australia | Boeing 737-800 |

| 14 hours | Melbourne, Australia | Dubai, UAE | Airbus A380-800 |

| 19 hours | Dubai, UAE | Auckland, New Zealand | Boeing 777-300ER |

I carried electronic environmental monitoring devices on board the airplane and observed the CO2, temperature and humidity levels recorded on the monitors during the various flight time/duration.

The aim was to explore the CO2 levels during each flight stage (e.g., boarding, dining, landing, etc., as shown in Figure 1 below) and review the available evidence on cabin ventilation.

My findings are explained by answering the five questions below.

How is an airplane ventilated?

Ventilation is the introduction and distribution of outdoor air into a space to maintain acceptable indoor air quality and minimise health risk.

Over the course of a flight, air is pumped from the ceiling into the cabin, then through the air outlets above the passengers’ seats, and behind the luggage compartments to ventilate the aisle. This air is then circulated in a circle back down towards the floor of the cabin and sucked out below the window seats.

The cabin air comprises of both conditioned and recirculated air. About 50 percent of air in planes is fresh outdoor air piped in from outside the plane, while the other 50 percent is recirculated air within the plane, filtered through a High Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) system1,2.

Most new and old refurbished commercial airplanes are typically equipped with HEPA filters of different grades, and I am not sure about which grade was used in my flights. Older commercial airplanes were generally ventilated with 100% fresh air, but the requirement during the 1980s to reduce airplanes operating costs led to the introduction of air recirculation systems2. That is the recirculated air is passed through HEPA filters, which are capable of capturing particles, but not CO2 molecules. As will be explained later, this suggests that cabin air may contain relatively high concentration of CO2 due to exhalation by occupants, but the HEPA filters will clean the air of particles. This means that CO2 might not be a good indicator of overall air quality and COVID-19 infection risk in airplanes.

Summarily, in airplanes, air is blown in from ceiling ducts and sucked out through vents near the floors. While the plane is cruising, the cabin air is refreshed roughly in about two to three minutes – which is a higher rate of cleaning the air, and passengers are constantly breathing a mixture of fresh and recirculated air.

What is my experience of air quality in planes?

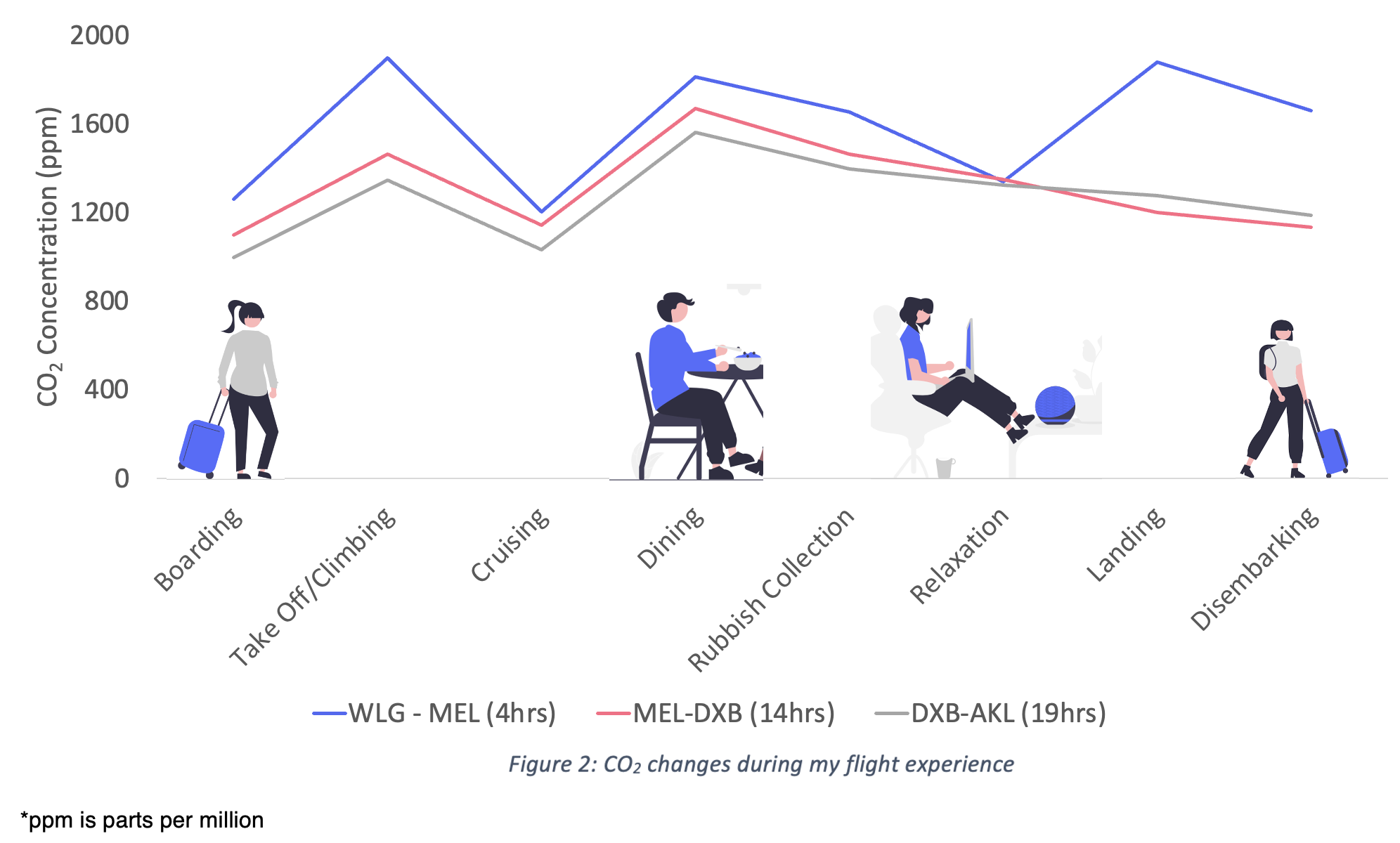

The visual timeline diagram below (Figure 2) presents the observed CO2 recorded in the eight stages of my flight experience.

CO2 is commonly used as a proxy for assessing ventilation effectiveness and it is measured in parts per million (ppm). Since the COVID-19 pandemic begun, a more stringent threshold of CO2 levels less than 800 ppm has been generally recommended as a very rough indicator for the use of comparing or ranking ‘good’ ventilation in some buildings.

As can be seen in Figure 2 below, the CO2 levels recorded in the airplanes were higher than 800 ppm in all flight routes and ranged from 900 – 1900 ppm. Outdoor CO2 levels is around 420 ppm and levels above this in indoor spaces, such as buildings is an indication of different spectrums of relative infection risk.

Though the CO2 levels recorded in all routes were above the recommended ‘good’ levels for buildings, it doesn’t necessarily translate to poor ventilation on these planes. This is because, in indoor environments, especially the airplane cabin environment, there is a significant difference between the behaviours of gases (CO2) and particulates1 (this is further explained in the next below).

Does high CO2 levels mean high risk in planes?

Within a plane, there are few sources of particulate generation. A study by Trent et al., (2022) states that “HEPA filters provide essentially particulate-free air, while gases such as CO2 passes directly through the HEPA filter to be recirculated into the cabin, and the airflow does not separate gases”. This implies that the evaluation of how gasses behave in airplanes cabin are thus not applicable to the study of particles in buildings.

Trent et al., (2022) further states that “the concentrations of gases emitted by passengers may be higher than those of particulates because gases are not removed by HEPA filters. However, the continuous downward airflow gradient (unlike the intermittent airflow in some buildings) keeps the time required to remove particles within the breathing zone of airplanes passengers short, and consequently there is no long-lasting, high concentration of aerosol particles in that zone”. In other words, because most new and old refurbished commercial airplanes are typically equipped with HEPA filters, the fact that CO2 levels appear higher than recommended in buildings is no reason to panic.

This is because, the recirculated supply air in airplanes is HEPA filtered and mixed typically with 50 percent outdoor fresh air, hence the air has no significant viral contamination since the outdoor air at cruising height (typical altitude of 30,000–40,000 feet) contains very few microbiological/infectious agents1.

HEPA filters are rated using 0.3-µm sized particles. Bacteria will most likely be removed by the HEPA filters because most bacteria have diameters of approximately 1µm. On the other hand, viruses are usually 0.01–0.10µm in size, and will usually be trapped in the filters, because viruses generally form clumps or attach to larger dust particles5. Thus, about 99.9% of bacteria and viruses produced by airplanes passengers are removed from the recirculated cabin air6,7.

Cabin air is essentially sterile because both the recirculated and air outside the airplanes are free of pathogens, and has a relative humidity of about 10–20% and a temperature of 18–30°C.

Also, because of the directional flow (circle of air movement from top to bottom, with little of any front to back flow) on planes, the seats partially compartmentalize the airflow, as it acts as additional physical barriers to help isolate passengers from each other.

Airplanes typically provide 20 to 30 air changes per hour (ACH), with airflow rates of 7 to 9.4 L/s of outdoor and recirculated air per occupant1,2. The high exchange rate on planes ensures that both outdoor (fresh) and recirculated (existing) cabin air is mixed evenly, with the goal of minimizing pockets of air that could become stale or linger for too long.

Therefore, the common misconception among passengers that if one person on board an airplanes has an infection, then all other passengers are at risk, may not necessarily be the case, This is because respiratory pathogens are diluted by frequent air exchanges, and passengers at most risk are those in close proximity to the infected passenger, with minimal risk for others1.

Virus transmission on airplanes may be through direct contact or short range aerosols, as opposed to airborne particle transmission. In reality, we don’t know the means of transmission except that if infected people travel, not everyone who shares the flight gets infected – indicating that instances of high CO2 in planes does not equate to higher risk, either due to the effectiveness of HEPA filtration, or that airborne transmission is just not the predominant transmission method on planes.

Compared to 5 to 12 air changes per hour in buildings such as offices and homes, cabin air is completely exchanged at least 20 times per hour, and this high air exchange rate further reduces the likelihood of transmission of viruses onboard.

When is air quality lowest on planes?

As shown in Figure 2 above, the air quality seems lowest during my boarding and disembarking experience. Though CO2 levels spiked during dining, this could be due to higher exhalation rate by passengers while eating and likely chatting.

Until the plane is in the air, rapid-air circulation and HEPA filters don’t work at maximum effectiveness during boarding and deplaning1,2. When a plane is on the ground sitting at the gate or idling, the stale warm air you seldom notice might mean that there is little circulation of air (ventilation may not be working at maximum effectiveness).

Therefore, during boarding and disembarking an airplane is when you’re most likely to breath the lowest quality of air compared to when the plane is cruising at high altitude. This might be due to the little circulation of fresh air during these periods and the likelihood of directly inhaling a cloud of infected exhaled air from another passenger.

Figure 2 also suggested that the highest CO2 levels was recorded in the shortest flight route/time. This may be due to the size and type of plane and the number of passengers on board.

Anecdotally, after air travel, people may complain of respiratory symptoms, but “studies on ventilation systems and patient outcomes indicate that the spread of viruses during flight occurs rarely”2.

Acquisition of infection following air travel could likely be associated with other factors inherent, such as low humidity, lowered barometric pressure and hypoxia4,5. For example, “breathing low-humidity air for prolonged periods could result in dry mucous membranes of the nose and throat, which can lead to respiratory tract infection”2.

In summary, studies that have examined contaminants in cabin air have found no evidence for increased disease transmission on board airplanes1,2,8,9. Although there is a widely held concern about air quality and transmission of respiratory pathogens on airplanes, studies on cabin ventilation and patient outcomes suggested that the transmission of pathogens occurs rarely. This is because:

- HEPA filters remove pathogens from recirculated air

- Outside air entering the cabin at high altitudes is essentially sterile

- Tempering the air (heating/cooling) further reduces pathogen risks

- The low humidity, laminar airflow pattern and high airflow rates and frequent air exchanges in the cabin further minimizes pathogen contamination onboard airplanes

When transmission does occur, it is more likely with pathogens spread predominantly by close exposure to an infected passenger, in which case transmission would likely occur regardless of the mode of transportation.

A study found no evidence of an association between the prevalence of infection and where a passenger seats, be it in the middle, window or aisle seats10. However, there is some evidence that passengers within two rows of an index case are at higher risk11.

Regarding COVID-19, studies suggest that COVID-19 may be transmitted during a passenger flight, but there is still no direct evidence, and the risk of in-flight transmission is considered to be very low, estimated at one case per 27 million travellers, based on published in-flight cases10,11.

What are other passengers perception of low air quality in planes?

During my journey, I interviewed one passenger in each route on their perception of when the air quality is lowest onboard an airplane. The interviewees were able to express the perceived air quality in a very clear manner. The air sometimes feel stuffy and warm when I am boarding the plane and securing my luggage in the overhead cabin, said a passenger on the Wellington to Melbourne route. Similarly, a passenger in the flight from Melbourne to Dubai explained how I feel stale air when I am boarding the plane and I fiddle with the overhead air vent in an attempt to get more air. The interviewee in the flight from Dubai to Auckland differed, stating that I feel the air quality is poor during dining, due to movement of the crew and the smell of food, with many passengers talking.

The subjective perception of passengers I talked to is consistent with the measured CO2 data (Figure 2). These responses are also consistent with those in the Atlas of Comfort12, where—even if people are not able to sense CO2 concentration—respondents suggests that they could infer air quality from a number of different environmental cues.

Overall, it appears the ventilation systems in airplanes are not always operating effectively during boarding, when it is parked at the gate, and this represents a time of higher risk. Therefore, it is recommended that a systematic evaluation of airplane ventilation during boarding and disembarking should be carried out, especially during pandemics.

Disclaimer

This article does not attempt to explore infection risk or the association and does not account for a wide range of variables that may impact cabin air quality, such as accounting for the number and movement of passengers up and down the aisles.

About the author

Dr Aniebietabasi Ackley (aniesity@gmail.com) is a sustainable architecture professional and scholar who is passionate about user-centred design and healthy and sustainable environments, with a focus on improving indoor/outdoor environments in schools, homes, offices, health care facilities, and recently, other related indoor spaces such as airplanes, buses and trains.

Reviewers

Dr Germán Molina – Buildings for People / SIMPLE simulation tools: With a background in Mechanical Engineering, Germán is passionate about helping to promote and understand what comfortable spaces are and has developed a model for understanding peoples feeling of comfort in indoor environments.

Dr Jason Chen – University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand: Jason’s background is in solving engineering problems using mathematical modelling and statistical methods, and has over the years been researching into the indoor air quality and studying infection transmission of airborne diseases.

References

- Trent, S., Davis A., Wu, T., Menard, A., Cummins, J., Santarpia, J., Olson, N. (2022). Inhaled Mass and Particle Removal Dynamics in Commercial Buildings And Aircraft Cabins, ASHRAE Journal.

- Leder, K., Newman, D. (2005). A Review of Respiratory infections during air travel. Internal Medicine Journal. 35 (50-55)

- Rayman RB. Cabin air quality: an overview. Aviat Space Environ Med 2002; 73: 211–15.

- Holland RB. Air quality on long flights. Med J Aust 1992; 157: 429.

- DeHart RL. Health issues of air travel. Annu Rev Public Health 2003; 24: 133–51.

- Dechow M, Sohn H, Steinhanses J. Concentrations of selected contaminants in cabin air of airbus aircrafts. Chemosphere 1997; 35: 21–31.

- National Acadamy of Sciences. The Airliner Cabin Environment: Air Quality and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1986.

- Brown TP, Shuker LK, Rushton L, Warren F, Stevens J. The possible effects on health, comfort and safety of aircraft cabin environments. J R Soc Health 2001; 121: 177–84.

- Brundrett G. Comfort and health in commercial aircraft: a literature review. J R Soc Health 2001; 121: 29–37.

- Guo, Q., Wang, J., Estill, J., Lan, H., Zhang, Wu, S., Yao, J., Yan, X., Chen, Y (2022). Risk of COVID-19 Transmission Aboard Aircraft: An Epidemiological Analysis Based on the National Health Information Platform. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 118: 270-276.

- Bielecki, M., Patel, D., Hinkelbein, J., Komorowski, M., Kester, J., Ebrahim, S., Rodriguez-Morales, A., Memish, Z., Schlagenhauf, P. Air travel and COVID-19 prevention in the pandemic and peri-pandemic period: A narrative review. Travel Medicine and Infectious Diseases.

- Molina, German (2022). Exploring, modelling, and simulating the Feeling of Comfort in residential settings. PhD thesis published by Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.